April 4, 2022

Pittsburgh’s hot housing market + Allegheny County’s largely frozen assessments = ‘fundamentally inequitable’ tax bills

Rich Lord

April 4, 2022

Pittsburgh’s hot housing market + Allegheny County’s largely frozen assessments = ‘fundamentally inequitable’ tax bills

Rich Lord

Part of the PublicSource series

How property tax assessments create winners and losers

Property taxes are supposed to reflect the values of the properties, but that’s no longer the case in parts of Pittsburgh.

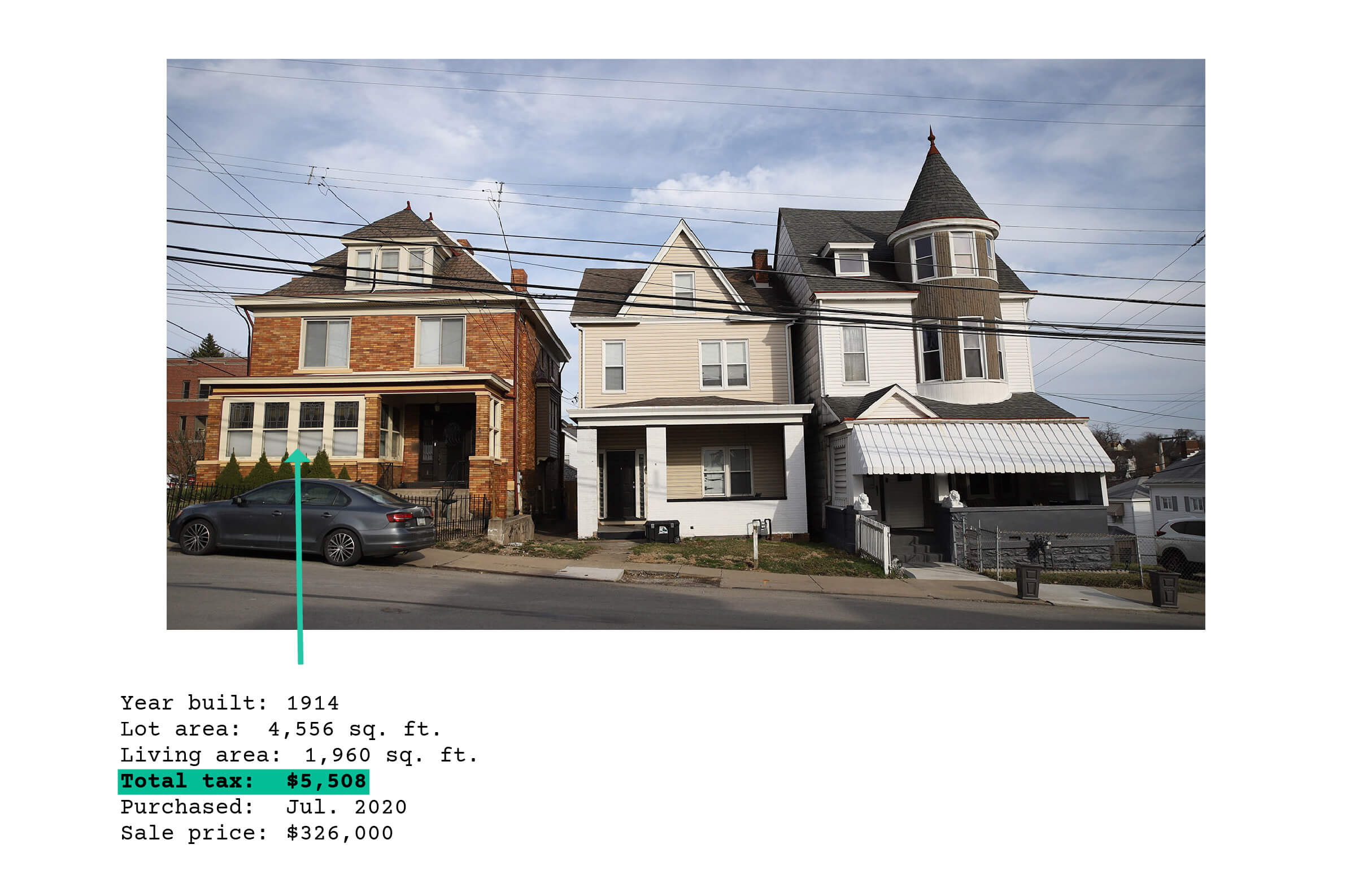

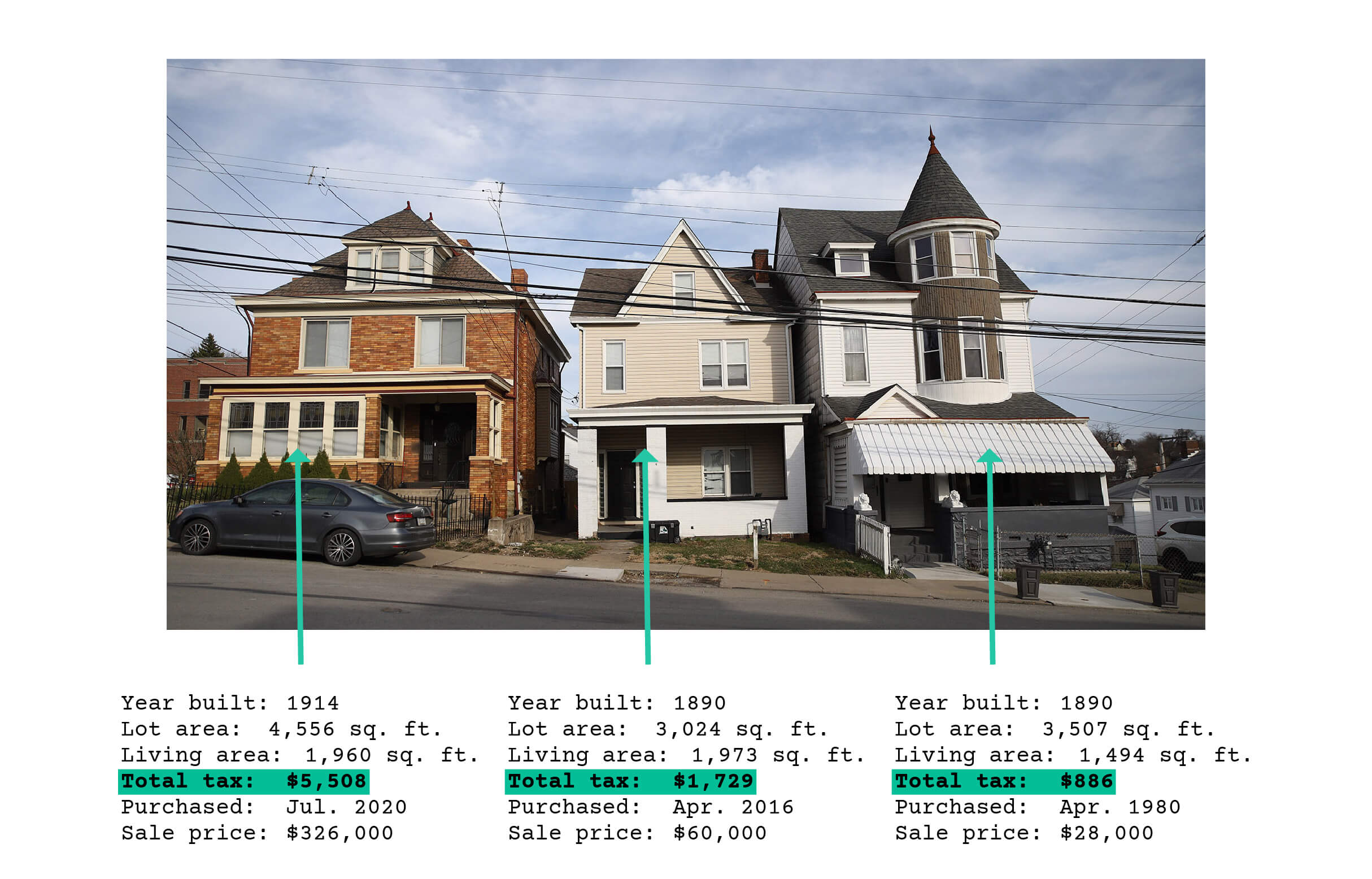

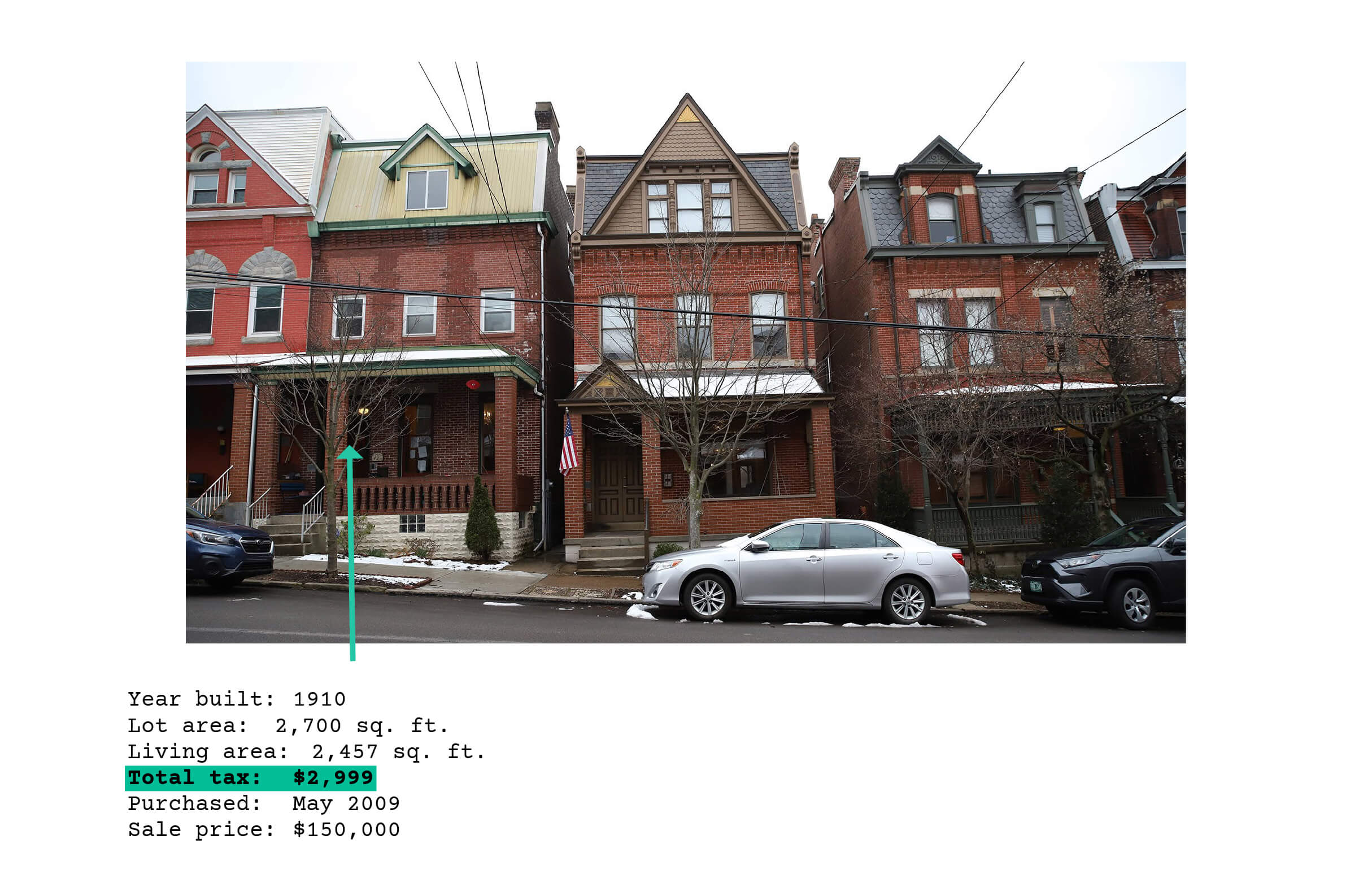

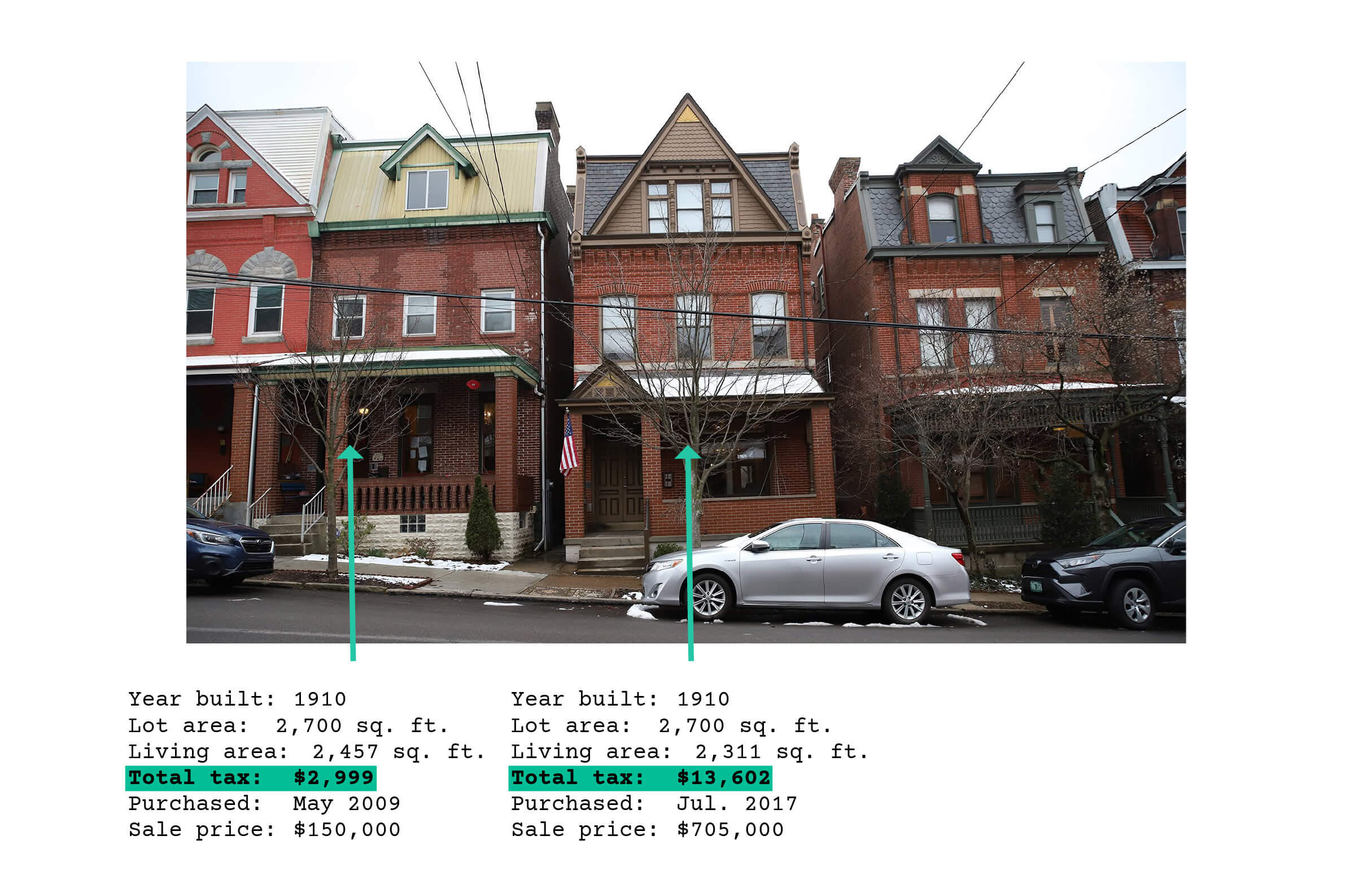

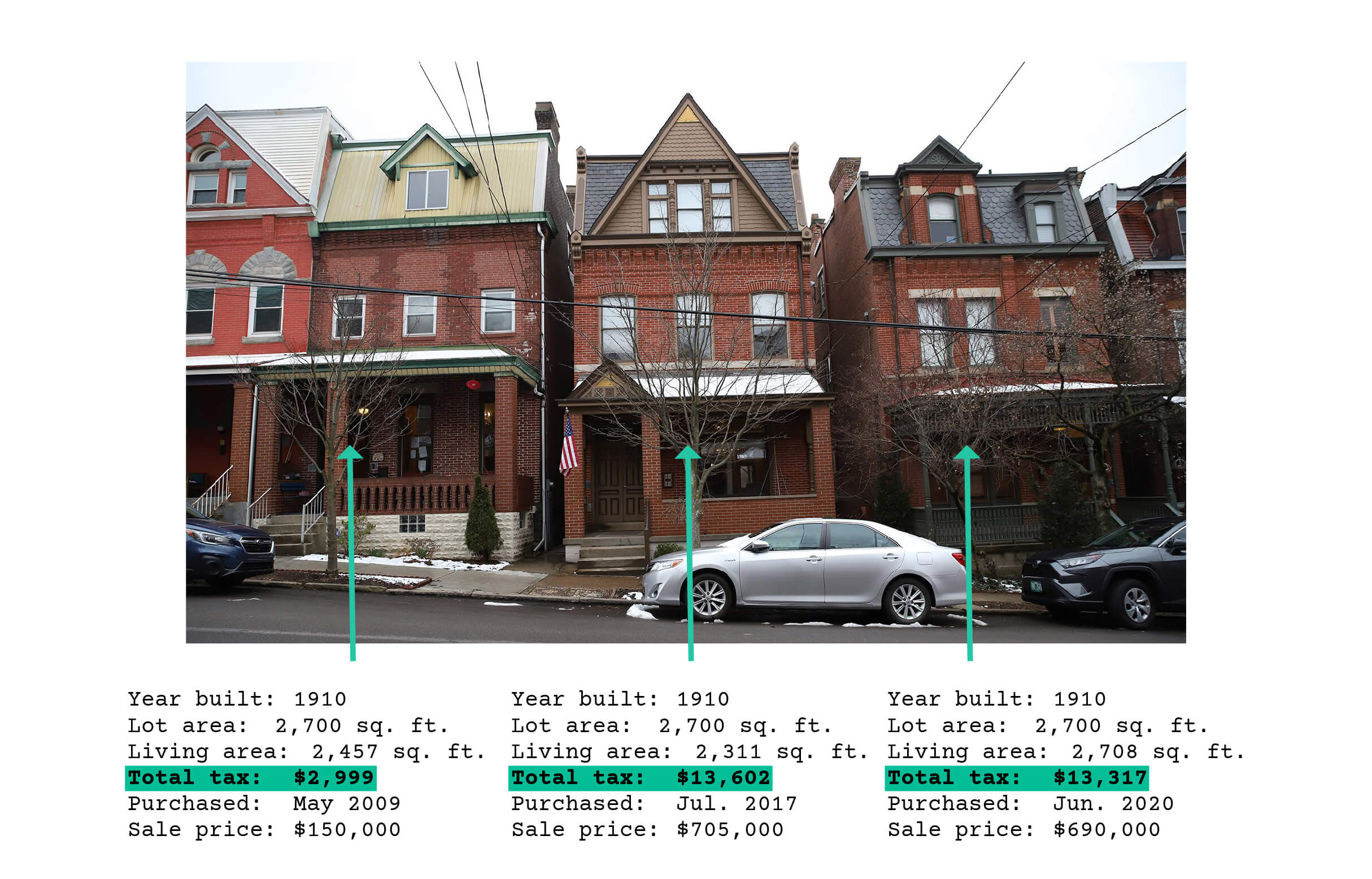

On the southern side of Mt. Washington, for instance, stand three similar houses with very different tax bills.

Richard Reiter bought one of those houses, featuring a shady porch and a turret, for $28,000 in 1980. His total property tax bill is under $900. “It’s good,” he said. “It could be lower.”

The house two doors down is around 30% larger — and gets a tax bill that’s five times higher. Reiter shrugged that off. “They paid a lot more for the house,” he noted.

Such chasms between tax bills result from the combination of rapidly rising housing prices, related assessment appeals and largely frozen valuations of houses that have not changed hands.

The county has, for a decade, used assessments of property values that it assigned in 2012 as the basis for the taxes levied on many homes and commercial buildings.

Properties that are sold, however, are often the subjects of assessment appeals filed by school districts or municipalities seeking more revenue. As housing markets have heated up in certain neighborhoods, some new buyers have been the subjects of appeals and have seen their assessments – and thus their tax bills – soar.

The county’s decision not to regularly reassess property has allowed assessment divides to worsen, said Pittsburgh Controller Michael Lamb.

“The more you stand still, the more unfair it gets,” he said. Without regular reevaluations of properties, “every 10 years or so, you get into this situation where you’ve got this horrible, unfair system of taxation.”

Reiter’s block is no anomaly. A few minutes’ walk away is Albert Street.

To be equitable, property taxes should be closely tied to the values of the taxed land and buildings. Pennsylvania’s constitution allows tax breaks for people based on age, disability, poverty, owner occupancy and length of residence, but broadly requires that those abatements, and the taxes themselves, be “uniform.”

It’s difficult, though, to envision a perfect way of taxing property with perfect uniformity.

“The government and we as citizens, we don’t actually know what property is worth,” said Christopher Berry, a University of Chicago professor and director of the Center for Municipal Finance. “Most people’s houses don’t sell every year or maybe not even every decade. So at any point in time, there’s a lot of uncertainty about what that house would be worth if it were to be sold.”

State law assigns counties the difficult job of assessing and taxing property. Traditionally, that has been done by periodically identifying, for each property, nearby “comparables” that were recently purchased in fair-market transactions. The property’s assessment is then based on those sale prices. While assessors in the past were expected to examine each home, some jurisdictions in recent years have turned to computer-assisted mass appraisal to improve efficiency. Philadelphia is in the process of implementing computer-assisted regular reassessments.

The state gives counties another labor-saving option: They can pick a “base year” at which values will be set indefinitely, and then consider subsequent sale prices as indicators of changes in the worth of properties.

Courts ordered Allegheny County to reevaluate the values of land and buildings in 2001, 2005 and 2012. Since then, County Executive Rich Fitzgerald has made 2012 the county’s base year, preserving assessments at levels set then, unless the owner, a municipality or school district files an appeal.

Fitzgerald, whose third and final term runs through next year, declined an interview request made through county spokeswoman Amie Downs.

What’s your assessment of tax assessments?

Email rich@publicsource.org your property tax story. We may publish it or contact you for more details.

School districts and some municipalities watch for property sales that are in excess of assessed values, and then appeal to the county’s Property Assessment Appeals & Review Board. That panel then decides whether to change the values.

Pittsburgh City Council in 2016 passed a resolution that largely put a halt to the city’s appeals. The school district, though, has filed a total of nearly 1,900 appeals on assessments of residential properties from 2017 through 2021, according to county data retrieved from the Western Pennsylvania Regional Data Center.

Each appeal involves time and expense, noted attorney M. Janet Burkardt, who works on the district’s filings with her law partner, Pittsburgh Public Schools Solicitor Ira Weiss. The firm also serves as solicitor for five other districts in Allegheny County.

“In order to make the appeal worthwhile, there has to be more than a 30% difference between the sale price and the assessed value,” said Burkardt. She said her firm typically does not appeal the values of properties sold for less than $200,000.

The district’s appeals sometimes follow sales by well over a year, creating some odd tax imbalances on Pittsburgh streets.

A South Side Slopes house, for instance, sold for $300,000 in 2015. A school district appeal filed in 2017 more than doubled the assessment and tax bill.

Last year, the larger house next door sold for $575,000.

Update (4/5/2022): Pittsburgh Public Schools last week filed an appeal of the assessment on the right house pictured on Brosville Street, purchased in September 2021.

Pending the outcome of the appeal, a house that sold for nearly double its neighbor’s price incurs half the tax bill.

When appeals are successful, the appeals board assigns a new assessment, based largely on the sale price. The board applies a discount, purportedly calculated to bring the new tax bill closer in line with properties whose assessments are still at 2012 levels. That process is the subject of a lawsuit in the Court of Common Pleas in which plaintiffs claim that the county is miscalculating changes in the property market, and that the discount should be much steeper.

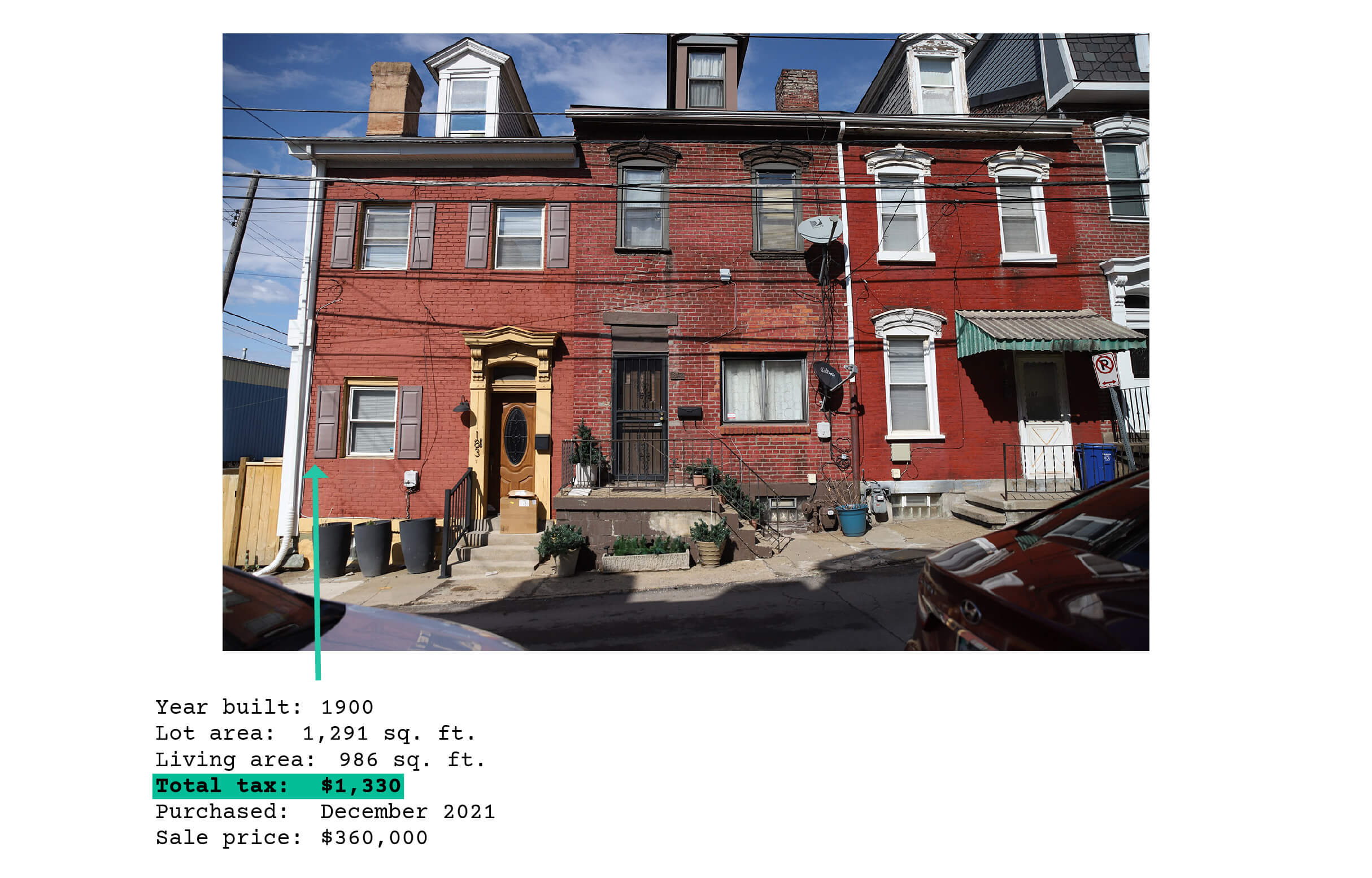

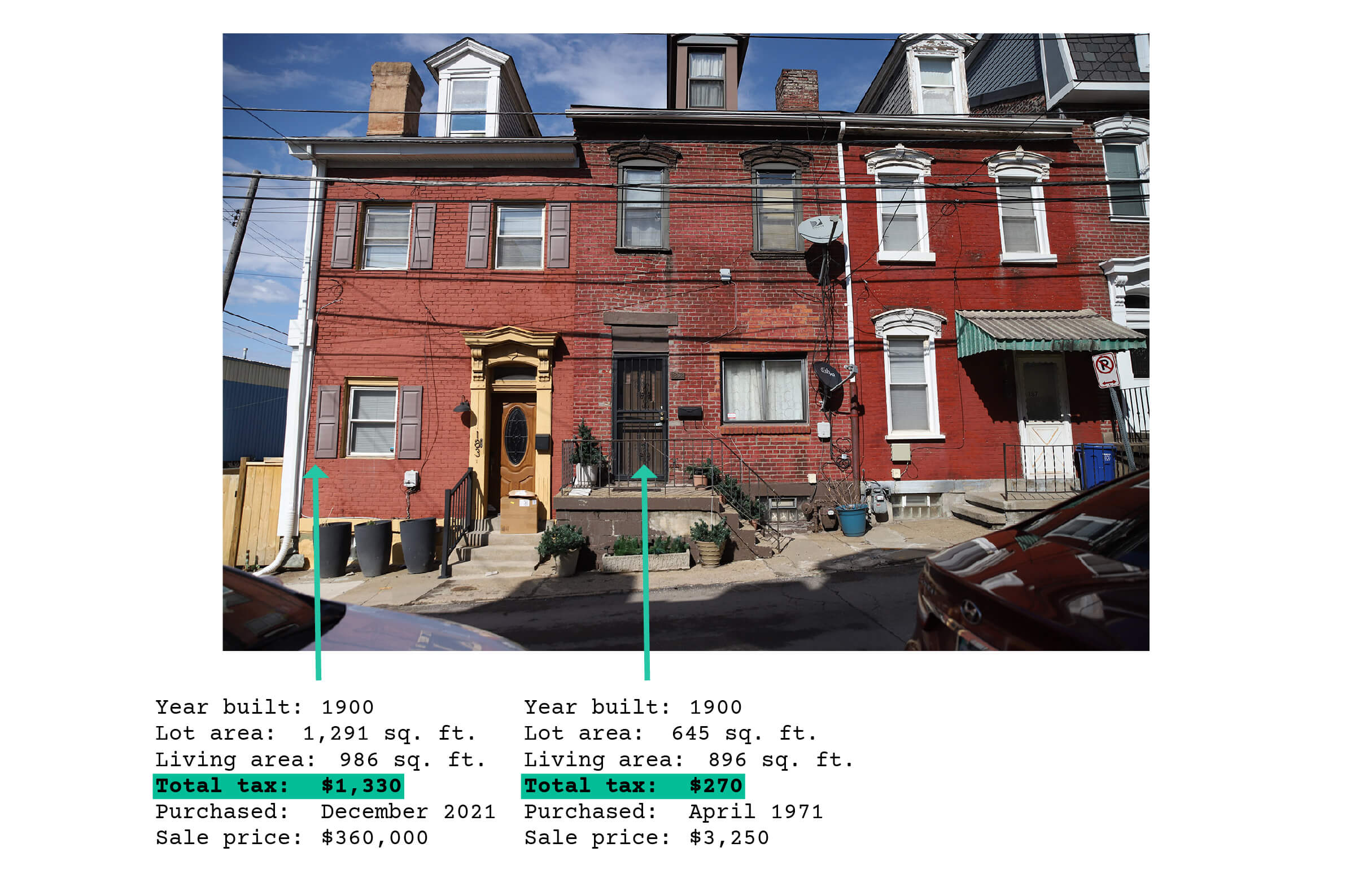

On Central Lawrenceville’s Fisk Street, a neighborhood’s sizzling housing market and the appeal process have created winners and losers.

Nancy Felix loves Fisk Street, but “wouldn’t object to our tax bill going down,” she said. She moved along with her husband to Pittsburgh in 2017 to work in university fundraising and alumni relations.

Her prior hometown, in New Jersey, conducted a reassessment. Would she welcome one here?

“It’s hard to say that I want other people’s taxes to go up. I certainly don’t want that,” she said. “But I recognize that when you look at the numbers, there is a lot of up and down, and a lot of inequities. So I guess I just want it to be fair for as many people as it can be.”

Nancy Felix stands outside her Lawrenceville home with her dog Ruthie. (Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

If the county decided to reassess, it would need to assign new tax values to the roughly 580,000 parcels within its boundaries. But neither the county, nor its municipalities or districts, would be allowed to pocket huge increases in revenue.

Laws at the state and county levels bar governments from using reassessments to reap windfall increases in their total property tax collections. As a result, if a reassessment boosted assessments, tax rates would have to come down to prevent a surge in collections. With assessments rising but rates falling, some tax bills would go up, while others would come down.

Walk 15 minutes down Butler Street from the Felix house, and you can get a sense of how steep those changes could be.

Through an appeal or reassessment, Zachary Burns could see taxes jump on his Lower Lawrenceville row house. (Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

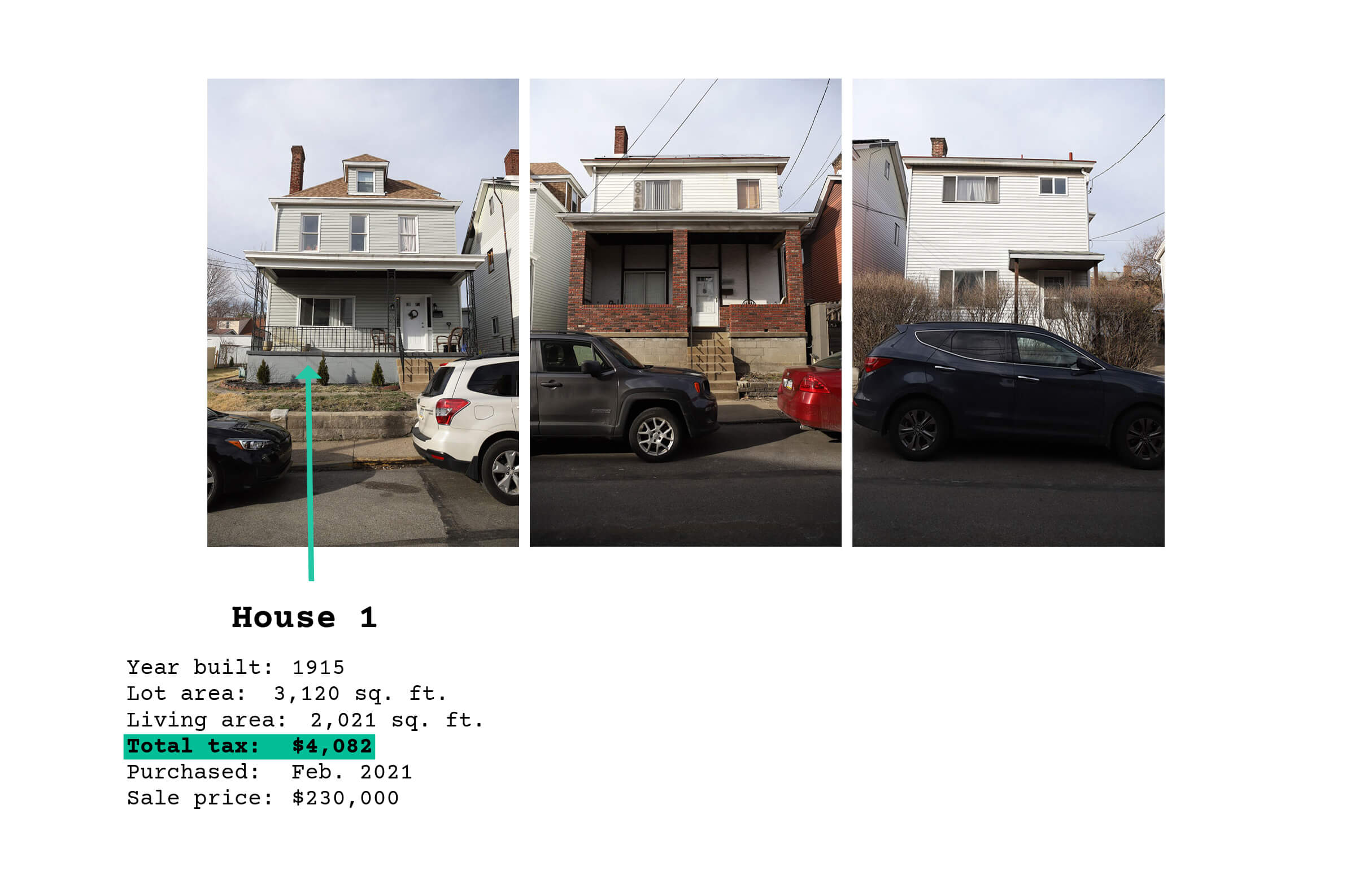

Software developer Zachary Burns and his wife bought a house on Lower Lawrenceville’s 34th Street in December. They loved the yard, perfect for Herman, their Bernese mountain dog.

The Burns house is less than half the size of the Felix house and cost half as much. Burns’ tax bill is one-tenth of Felix’s — so far.

His purchase price was six times the county’s assessment, potentially making it a target for a school district appeal.

Burns said he hadn’t thought much about the possibility of an assessment appeal. If an appeal resulted in a big jump in his tax bill, “it wouldn’t be great. If that goes up six times, that wouldn’t be ideal. We would be able to afford it, but we would have to cut some other things out.”

A reassessment of every property, if it pushed assessments close to market values, could have an even more dramatic effect on the tax bills of Burns’ neighbors. Their houses have been in their families for decades and have even lower assessments.

“I don’t understand the logic” of wildly different property assessments, said Burns, when told of his neighbors’ tax bills. “I’d like to know that there was more uniformity to the process.”

Controller Lamb predicted that the lack of uniformity will eventually put the county back in court.

“There’s going to be a [legal] challenge to the fairness of assessments,“ he predicted. That will spur another reassessment, and the longer the delay, the bigger the resulting changes will be.

Randall Walsh, a University of Pittsburgh economics professor and housing expert, said other states, like Colorado, adjust assessments annually or biennially, based on neighborhood-level property sales data. Allegheny County’s decision to retain decade-old values results in “fundamentally inequitable” variations in taxes.

“Politics are part of why we don’t do things right, because politicians are afraid of the backlash that happens when you see large adjustments in property tax rates,” said Walsh. By failing to reassess for a decade, he added, the county “is locking in that sort of unhappiness and unease for down the road when we have to have another big adjustment because we haven’t been keeping up.”

In neighborhoods like Lawrenceville, where longtime homeowners live next to better-off newcomers, a reassessment could be “heartbreaking“ in its effects on lower-income residents, Lamb said. “So how do you protect those people?”

He said state legislators could change the law and allow counties to limit the amount that a given person’s tax bill could rise due to reassessment.

If that doesn’t happen?

“We‘ve got a horrendously unfair system of taxation,” he said, “and when we try to fix it, we’re going to be hurting the people who least can afford getting hurt.”

Note - Total tax includes Pittsburgh Public Schools, City of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County property levies, based on the Allegheny County Real Estate Portal and City of Pittsburgh Property Tax Worksheet.

Rich Lord is PublicSource’s economic development reporter. He can be reached at rich@publicsource.org. or on Twitter @richelord.

Photos by Ryan Loew and Kaycee Orwig. Visible house numbers have been blurred for privacy.

This story was fact-checked by Abigail Nemec-Merwede.