May 25, 2021

At the end of last summer, Anthony Kane was offered his dream job.

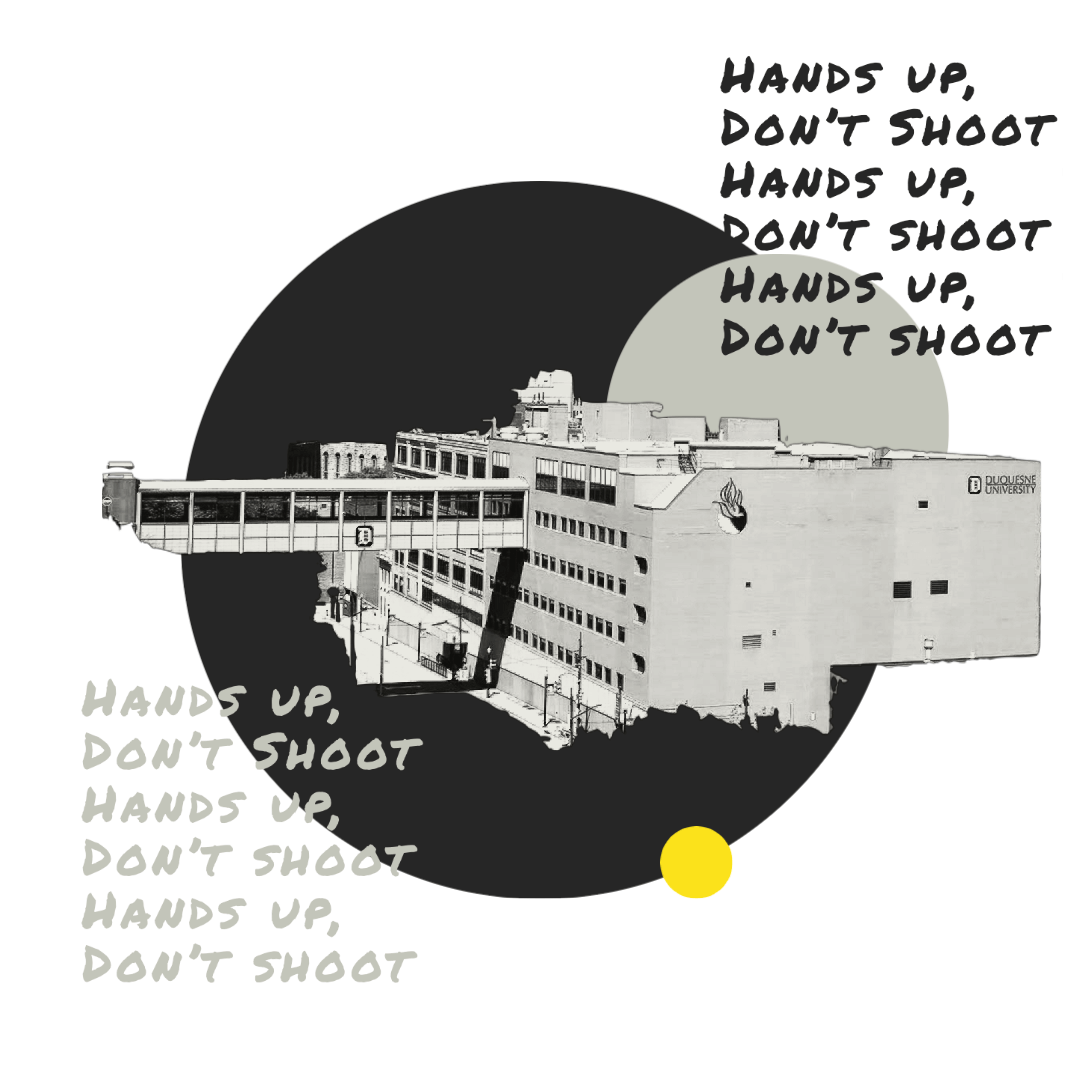

He spent the previous eight years managing residence halls and staff at Duquesne University. Now, the college was tapping him, a 31-year-old Black man, to be its new director of diversity and inclusion.

It was not going to be easy.

The murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis spurred months of protests and calls for racial reckoning across institutions. Students were already grappling with the grief of a global pandemic and anticipating a tense presidential election that would set the national tone on social justice reform.

Before Kane’s first day, he reached back to connections he’d made with student leaders at clubs like the Black Student Union. He wanted to hear what they thought needed to be done.

“The first thing I knew was I needed to fit into this role from an authentic space,” Kane said.

Anthony Kane. (Courtesy photo)

Students wanted to be included in his work, to participate in planning programs and events meant to make the campus more inclusive, not just receive emails about negative incidents on campus.

Kane’s challenge is one facing university leaders across the country. As universities respond to calls for reform, staff in diversity and inclusion offices can be a powerful connection between institutions that are often siloed and slow-moving and the students demanding changes in campus culture.

Yvette Alex-Assensoh, a national voice on equity work from the University of Oregon, said colleges and universities need to go beyond statements and realize that all levels of the institution impact equity — from the final decision-makers to the types of research conducted and how and what students learn.

“We need to make sure that we are the kind of institution where we are not symbolically and proverbially having our knees on the neck of students, staff and faculty members because we’re not hearing that they can’t breathe,” said Alex-Assensoh, who serves as the university’s vice president of equity and inclusion.

A year after the start of protests for racial justice, PublicSource examined diversity and inclusion efforts at four Pittsburgh-area campuses and how staff are working to empower students.

Kane quickly realized his work would intersect with his own experiences. To help others overcome a challenging year, he set out goals for his new role while also practicing self-care.

That’s an issue facing staff at other universities as they balance their own realities as members of marginalized communities while trying to bring meaningful change.

As a Black woman with Black children, Ayana Ledford did not see Floyd’s murder as one exceptional act of violence but as a tragedy that has happened countless times before.

“So it wasn’t brand new for me,” said Ledford, who will be promoted in July to associate dean of diversity, equity and inclusion in the Dietrich College of Humanities and Sciences at Carnegie Mellon University. “It wasn’t some brand new heartbreak of racial divisions in our country. It has always existed.”

Ledford realized the protests for racial justice also showed the university’s majority-white population how anti-Blackness can result in tragedies like the killings of Floyd or Breonna Taylor in Kentucky.

Ledford saw her own college community stand up and seek out ways to help.

“It provides an opportunity, in essence, that I end up with an increase of individuals wanting to participate,” she said.

Faculty and staff were already working on the college’s strategic plan for diversity efforts for the next five to 10 years, but the events of last summer expedited the process. After consulting with 20 faculty members and 200 students, the college published the plan focused on “recruiting, retaining and cultivating a diverse, equitable and inclusive community.”

The college reviewed its hiring process to expand the pool of candidates and tried to redefine its role in the community by investing in outreach efforts. For example, the college created a program called LEAP, which will focus on arts and humanities for students at schools like City Charter High School to attend courses with college students. Ledford said the goal is to offer mentoring and build community relationships so Pittsburgh students consider CMU when applying to colleges.

At the heart of it all, Ledford said the college has to ask a vital question: What is the role of an academic institution?

If given the right resources, Ledford said students will learn from others and become critical thinkers. But until Black students feel fully accepted and safe on campuses, she said she stays up at night thinking about what could happen to her own children.

At Chatham University, Darlene Motley, the dean of the School of Arts, Science & Business, said the past year has been difficult.

In April, the country watched the trial of Derek Chauvin, the police officer who knelt on Floyd’s neck for 9 and a half minutes. In that time, more incidents of police brutality occurred — even during the trial.

Motley said she still had to get through her daily routine but kept thinking about what else she could do to support her community. As she waited for the verdict, she agreed with what broadcast political analyst Van Jones said about how many other people of color woke up that day too scared to be hopeful.

“I’m a wife and a mother of Black men. That plays in my mind all the time — wanting to make sure people are treated fairly and carefully. When do we get to the point where we don’t have to worry about walking down the street and what that might mean?”

Darlene Motley is the dean of the School of Arts, Science & Business at Chatham University. She co-chairs a university council which has helped address issues of gender, LGBTQI rights and new initiatives after last summer’s racial justice protests.

(Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

Five years ago, Motley had approached the university president with an idea. She wanted to bring together voices of students, staff and faculty to advise the president on issues of diversity and inclusion.

She now is co-chair to that council, which over the past four years has helped address issues of gender, concerns that some students have felt objectified and supporting trans students and LGBTQIA rights.

The tragedies of the summer sparked more initiatives.

In the council, Motley and others have been gathering concerns and comments from students, offering training sessions on how to be a good ally and acknowledging white privilege and reviewing faculty recruitment efforts.

“I’d say we’re starting to move the needle in terms of how we recruit, how we look at issues when they arise,” she said. “But equally, there’s still a lot to go.”

The work of diversity, equity and inclusion [DEI] offices has been in the spotlight lately, but the work has evolved over years.

Since 1968, Ralph Proctor has been a professor at many Pittsburgh colleges and universities like the University of Pittsburgh, Chatham and Duquesne. His work in civil rights and in education also placed him in a vital position as some institutions realized they needed to do more.

In the early 2000s, he was approached by Community College of Allegheny County to create an African American studies program. Though he was initially hesitant, joking about wanting to retire and hang out on his front porch, Proctor saw an opportunity.

At the time, departments dedicated to ethnicity, race and gender were more isolated and susceptible to budget cuts.

“What we ought to be looking at, rather than simply Black studies, is a department that deals with the concept of ethnicity and of all cultures,” Proctor said. “Approach it as the building of a department that dealt with multiculturalism.”

His efforts to institutionalize the department meant that students had more opportunities to take classes about different cultures and identities. Proctor’s work paved the way for the community college’s Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, and he later served as chief diversity officer. Among other key tasks, Proctor helped review possible biases on campus and examined the hiring process to see what needed to be done to ensure the office could be effective.

“We are helping to develop the leaders of the future. And if we don’t tell our students the truth, they’re ill-prepared to deal with what’s going on in the world,” he said, referencing societal pitfalls like sexism or racism.

Now, Proctor works on several committees dedicated to diversity initiatives on campus. His approach to go beyond one department is also reflected in the current work of DEI offices.

Alex-Assensoh said DEI offices were initially focused on compliance, particularly related to affirmative action and Title IX, the 1972 federal law prohibiting sex-based discrimination. But over the years, officers have shifted their focus to issues of access and equity for students and staff, she said. Successful initiatives involve more than one office and must build support from students, faculty, the community and, crucially, university leaders and trustees.

“The board has final authority, and they have the right to say what is important, what are the priorities,” she said.

Alex-Assensoh said the University of Oregon integrated concepts of inclusion, diversity, evaluation, achievement and leadership. And now, she encourages colleges to really think about why DEI work exists.

“We can do the work and not really be motivated in our hearts to actually be changed. We just do it as sort of checking off a box or because we think it’s the right thing to do, but we really don’t understand,” she said. “We haven’t really thought about our own complicity, our own work, our own role in inequity, in discrimination, in racism, in heteronormativity and patriarchy.”

As the country marks one years since Floyd’s murder, Kane said he keeps his focus on the students.

At Duquesne, they wanted consistent communication that went beyond statements about racist incidents, like a professor using the n-word in class, but also about programming and events. In the fall, Black student organizations participated and organized events as part of “Black Culture Awareness,” a new initiative to celebrate identity and cultures outside of the traditional events hosted in February.

Kane also worked with the university to help streamline the bias reporting mechanism so that the college community knew exactly where to go if an incident occured. The office also changed its name to Center for Excellence in Diversity and Student Inclusion to reflect the work being done and the students. Kane said he is especially proud that his office moved from the basement of the student building to one of the top floors — a symbolic shift in acknowledging its importance.

Despite the weight of the work, Kane knew it was important to the students for him not to give up.

“It took a lot of self-reflection and emotional intelligence to really understand how to keep myself mentally stable throughout this exciting journey,” Kane said. “I love my job to death, but it has its challenges because I’m often living what I’m helping students go through.”

On his desk, he said he kept up a running list of demands from students and others to keep himself accountable.

“The one thing I wanted to do was get through the year, knowing and feeling that my students woke up every morning knowing that someone was fighting for them.”

Naomi Harris covers higher education at PublicSource, in partnership with Open Campus. She can be reached at naomi@publicsource.org.

This story was fact-checked by Matt Maielli.