Unmasked: Candid reflections on a warped year of COVID school in the Pittsburgh area

March 22, 2021

March 22, 2021

March 22, 2021

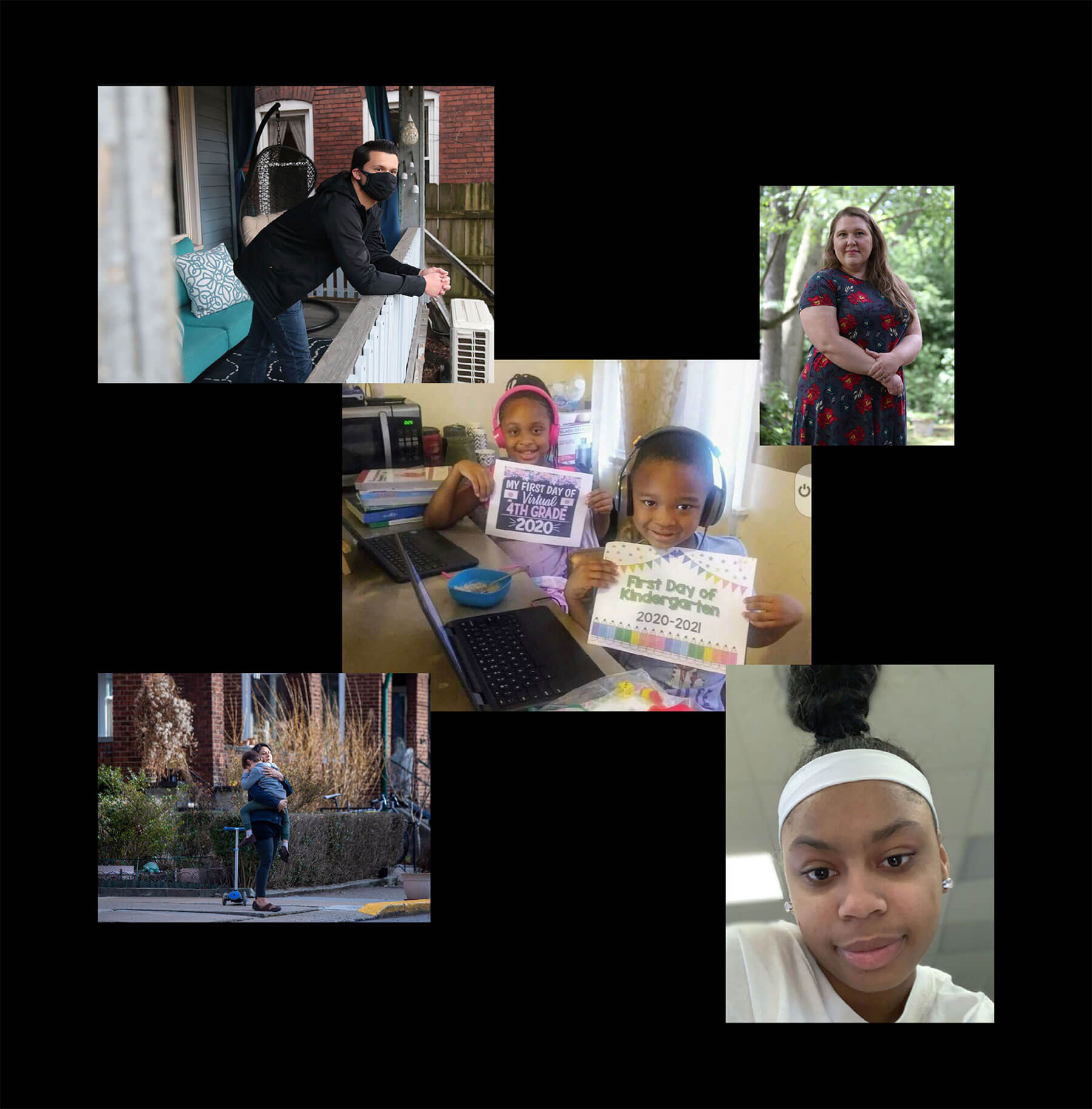

School days — in any other year — often include rambunctious chatter on school buses, leaning on lockers to catch up with friends and gossiping in a noisy cafeteria over lunch trays. But for many students across Allegheny County and beyond, this March morning began much more isolated, maybe alone or maybe with a parent beckoning them toward their laptop and headphones, likely in their home, at a learning pod, or masked and social-distanced in a school building.

It’s been a tricky, demanding year for everyone in the education community since schools first closed in March 2020. Parents are committing the ultimate juggling act in many cases, balancing facilitating learning with parenting and jobs. Students are navigating newly created virtual learning environments and striving to succeed. Educators have stretched themselves to teach beyond a physical classroom and are filling in gaps to help students at every turn — in some cases even delivering technology and meals to students.

A year later, many are still brimming with worry and anxiety about what’s next for local education. But they’re also clinging to hope. They’ve survived and persevered this long, after all.

One year after teachers and students across Allegheny County left their brick-and-mortar school buildings, PublicSource spoke with more than a dozen students, parents and teachers. Here are some of their stories.

Read their reflections on the last year

It’s been a roller coaster of a year for Theresa Schroeder and her three kids since schools first closed in March 2020.

Early on, it was really bad because her kids were relying on paper instructional packets. “They weren’t really learning anything.” Her children were also devastated by losing a sense of normalcy in a blink.

A year later, she said her 18-year-old senior and 15-year-old sophomore (who attend Pittsburgh Public Schools) and her 12-year-old 7th grader (who attends private school) have come to accept the situation.

And that concerns her.

“As a parent, I just feel like I’m constantly worried about somebody. And I do think with teenagers, a lot of it is just their mental health, like worrying about, ‘Do they feel despair?’”

School itself is better because they are being taught the class curriculum, but the remote learning experience is monotonous.

“Every day is the same,” Schroeder said. “They get up super early and sit in front of the computer and they’re pretty much sitting in front of that computer until like 2:45.”

In a typical year, her kids’ schedules would be packed with practices and performances for orchestra, band and sports. “The school district has done very little to help the kids who are involved in the arts actually participate in their activities like sports seem to be able to,” Schroeder said.

Her son, who is a senior, is missing out on final band performances and other lasts.

“There’s a lot of grief there, but we don’t really talk about it because it’s just what can you do? There’s nothing you can do,” she said.

Shroeder believes children are resilient but she worries about the way this time could change her children.

“There was a lot of loss,” she said. “I don’t know what the long-term effects of all that are going to be … That’s something none of us know.

“I think in some respects, it’ll shape them in a very positive way because I think they’re going to be so tough,” she said. “And I think it’s going to be clear to them what kind of world they want to live in. I don’t think they’re going to take things for granted the way maybe other generations did.”

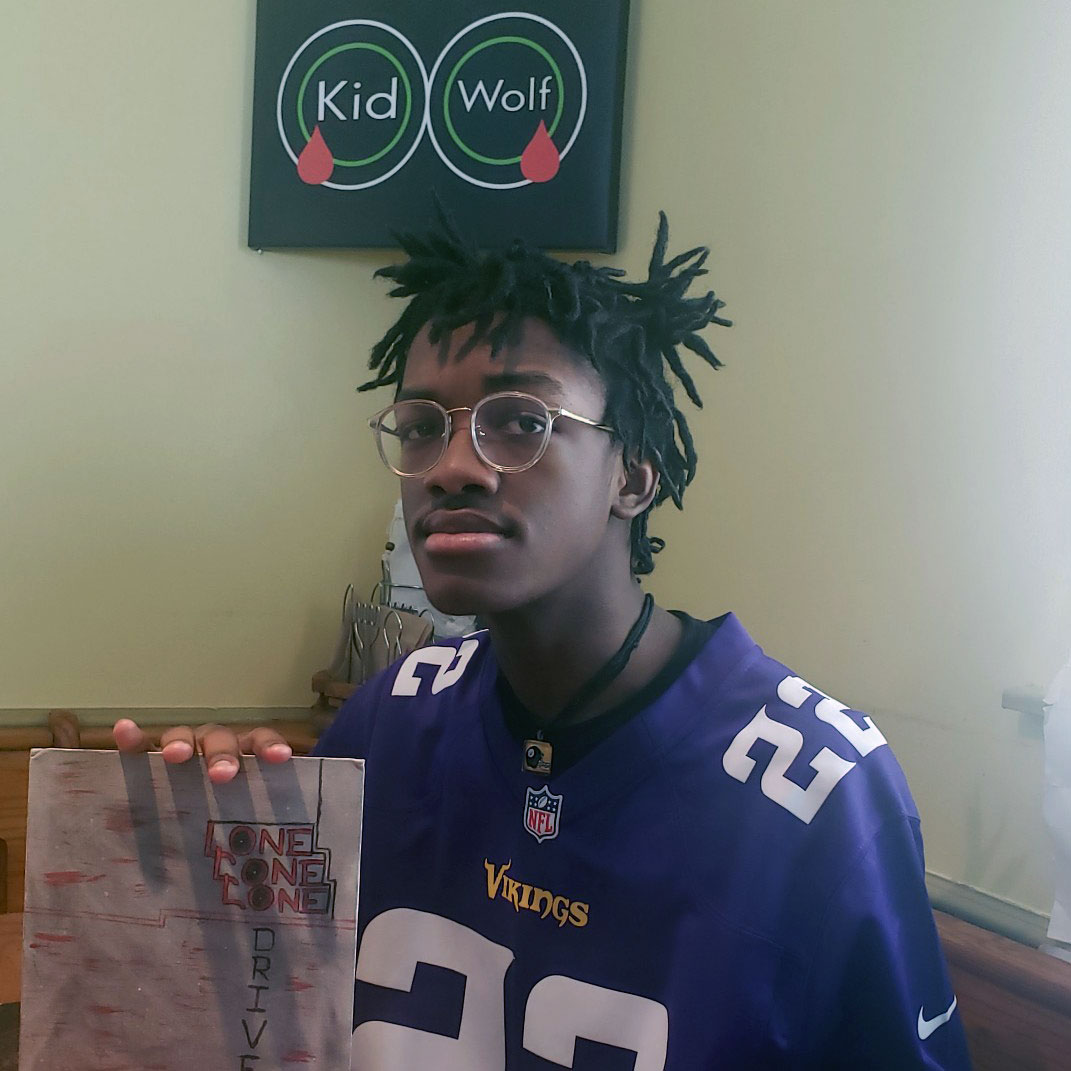

Allderdice senior Mason Brooks feels failed by the school district this year and describes it as the hardest time of his life.

“It was bad. It heightened my anxiety and now I’m afraid of not graduating,” Brooks said. He said he’s not the only student he knows on the verge of not graduating.

From the stress of having to keep afloat this year to failing classes that he’s never failed, he’s fed up.

“The district,” he said, “doesn’t care about the wellbeing of their students.”

While he’s tried to reassure himself his school career will be fine, to watch his grades decline has been difficult. “It hurts and it chips at your soul.”

He said students don’t have the support they had before COVID struck.

His takeaway, a year later?

“The school system, especially public, sets students up to fail and only cares about numbers, test scores.”

When it came to choosing a college, Chloe Werner wanted nothing more than to step foot on an actual university campus.

Since she was a little girl growing up in Pittsburgh, she dreamed of moving away and living and studying in a big city somewhere.

And while she still clings to the dream, it’s a bit more intimidating now, she said. COVID upended her senior year at Allderdice and her planning for college.

“I realize that probably in like six months I’m going to be moving to a major city that I’ve never seen before to stay on a college campus that I’ve never visited,” Werner said. “I sort of thought I would have a better idea of where I was going.”

It scares her.

“I can’t go to a campus and walk around and see if the kids there look happy to be at that school, like if people are smiling or if everyone looks really sad,” Werner said. She can’t visit professors’ offices or meet students face to face.

She traded campus tours for online forums and Google or Quora, where she scours message boards for college students giving feedback and reviews and dorm tours. But there is only so much you can get online.

She’s attempted virtual tours but doesn’t think they’re helpful. After a while, she felt like every college started to say the same things.

Though she’s deep in her college search, she still mourns what she lost during her senior year. Prior to the pandemic, she really loved school. “I really like learning things,” she said.

But full-time remote learning leaves much to be desired. “And it kind of takes away from your motivation. And I think sometimes it’s something that kids have a hard time expressing to their teachers,” Werner said.

She misses seeing friends between classes, study sessions after school, running into friends at the library.

“There was just a general environment that encouraged you to want to actually learn and want to understand things. And now I’ve lost that quality,” she said.

Not making the situation better is what she called a lack of communication from leadership at Pittsburgh Public Schools [PPS].

“Not knowing what to do is not an excuse for just not communicating with teachers or students or parents, because this is not right,” she said. “For PPS, maybe making these decisions is just their job, but for us, it’s like our life. I feel like these decisions affect so many people that we should have a lot more like clarification and input.”

Bethany Hemingway Klobuchar is in the final stages of a slow, nerve-racking waiting game that extended at least half the school year. She and her 7-year-old daughter Zora are awaiting a decision from the Keystone Oaks School District on her updated special education status.

In the meantime, Zora is effectively “shut off,” Klobuchar said — not in school and not in the hybrid-learning environment they chose at the start of the school year. Zora cannot learn online, even her private therapist agrees, her mom said.

“She needs the most maximum days in school to have that engagement. Online creates the most anxiety for her.”

Zora was officially diagnosed with a reading disorder in late February, months after Klobuchar first saw signs something was wrong in October — which she’d initially chalked up to regression from the spring and summer.

Zora would sometimes write letters or numbers backward. When Zora didn’t outright refuse reading, it would spur anxiety attacks.

“It’s kind of frustrating as a parent to see your child struggle every day and cry every day and there’s nothing you can do,” Klobuchar said.

During those anxiety attacks, Zora sometimes curls in a ball or hides behind the couch. Klobuchar said she often needs to help Zora to return to learning.

“It’s just been a very sad year just watching my child pretty much fall apart,” Klobuchar said.

Zora Klobuchar, 7, a second grader at Myrtle Avenue Elementary School in Castle Shannon, does school work at home. (Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

She and Zora are not alone, she said. Many parents she’s spoken with are noticing behaviors that they don’t typically notice in their kids.

Keystone Oaks School District reported about 17% of its 2019-2020 student population were enrolled in special education.

While the wait is winding down, it could still possibly be the end of the school year before her supports are in place, Klobuchar said.

“We don’t want her to be held back a year because of something that was not in her control.”

Bethany Klobuchar is a program officer at Staunton Farm Foundation, which funds mental health reporting by PublicSource. The selection of Bethany’s vignette was made independently.

For April Clisura, the pandemic revealed many new insights into her 6-year-old daughter’s education. With her daughter attending Greenfield PreK-8 in full-time virtual learning, Clisura said she has been able to spend more time with her daughter than ever before.

“It was interesting to see how they teach phonics, you know, and help kids learn to make their letter sounds,” Clisura said.

Clisura has watched her daughter progress in the virtual learning environment over the last year.

“My daughter actually prefers learning at home,” Clisura said. “At least at this age, she’s a little introverted, so whereas last year the teacher was telling me as a kindergartner she didn’t speak up in class and didn’t have a lot to say at all, I’m seeing her now as a first grader, especially as the year went by, she’s actually more comfortable speaking up and more talkative.”

Greenfield PreK-8 is part of Pittsburgh Public Schools, which plans to start hybrid learning for some students on April 6.

Clisura won’t be enrolling her daughter for in-person learning until next year.

“I’m going to wait until September because I feel like a lot more people will be vaccinated, but also because I know that there are not enough seats in the classroom.

“So I know that I am going to, like, feel better saying that, ‘Hey I’m someone who can stay home. My daughter’s doing OK with it, we’re doing OK with it.’”

Clisura said she agrees with the district’s strategy to prioritize kids who struggled with virtual learning to be in the classroom instead of reopening on a first-come, first-serve basis.

“I think, for equity reasons, we can’t just have the sole criteria of the parents’ preference if we’re going to really try to be equitable and not exacerbate whatever gap in learning has come about this year.”

While it may raise an eyebrow for some that 11th-grader Briayelle Gaines sought out employment smack in the middle of virtual learning amid COVID, Gaines has bigger concerns.

She’s worried about her mom. How will she continue to manage raising three kids by herself in an ongoing pandemic?

To help out, Gaines — who isn’t comfortable yet going back to brick-and-mortar school buildings — got a full-time job at Chick-fil-A to juggle school with supporting her single stay-at-home mom.

She sees all that’s going on in the world and wants to help, the 16-year-old explained.

“Everything that’s affecting our parents, it bounces off back on the children because if our parents are not getting no income or if our parents can’t feed us, it bounces back on us,” she said. “They have this weight on them that they can’t do nothing about.”

Her sister, 17, also works a full-time job while their mom cares for their 1-year-old brother.

Briayelle left her previous job at McDonald’s at the start of the school year because she didn’t want to risk her family’s health, especiall her brother. Once cases started to drop and the Chick-fil-A in Homestead was hiring, she jumped at the opportunity.

Full-time online learning is a chance to practice making her own schedule and balancing responsibilities — skills she said she will need to achieve her plans of becoming an entrepreneur when she graduates from West Mifflin Area High School.

When school resumed in September, she didn’t like virtual learning at all. The semester started off slow, but before she knew it: “They just piled all this stuff on us and expected us to get it done because it needed to be on their time.”

“I didn’t like it because it just, it felt like they were rushing things, like they were doing it to benefit them and not us,” she said. “They just wanted to get something out there just to get it out there.”

As an honors student, she said she expected the school work when classes resumed in the fall to be harder but in many ways, to her it was too easy. At the same time, she wishes the curriculum was more in touch with life outside of school and built in teaching more about Black culture as well as life skills, like how to pay bills or file taxes.

“I’m a person who likes the challenge and who actually does like to learn stuff and educate myself,” she said.

Changes need to be made, she said.

She hopes that the people in charge will start listening to Black community members.

“Because what’s a school without diversity?” she said.

Written by TyLisa C. Johnson

Last July, 10th-grade English teacher Amy Galloway-Barr was shaken by the impending return to school. In the rawest way she could, she plainly told PublicSource:

At the time, nine months ago, COVID-19 cases were on the rise and her concerns about the forthcoming school year — her 17th year in the classroom — were growing by the minute.

When Galloway-Barr spoke to PublicSource most recently, in February, it was just two days after her first COVID vaccine. She said that while remote, virtual teaching is completely different, it wasn’t as bad as she thought it would be.

“I was really worried that it was going to lose all of the personal interactions that you have with kids that make it really fun,” said Galloway-Barr, who teaches at Taylor Allderdice High School. “And I found out that that was not true. I still feel really connected to my students.”

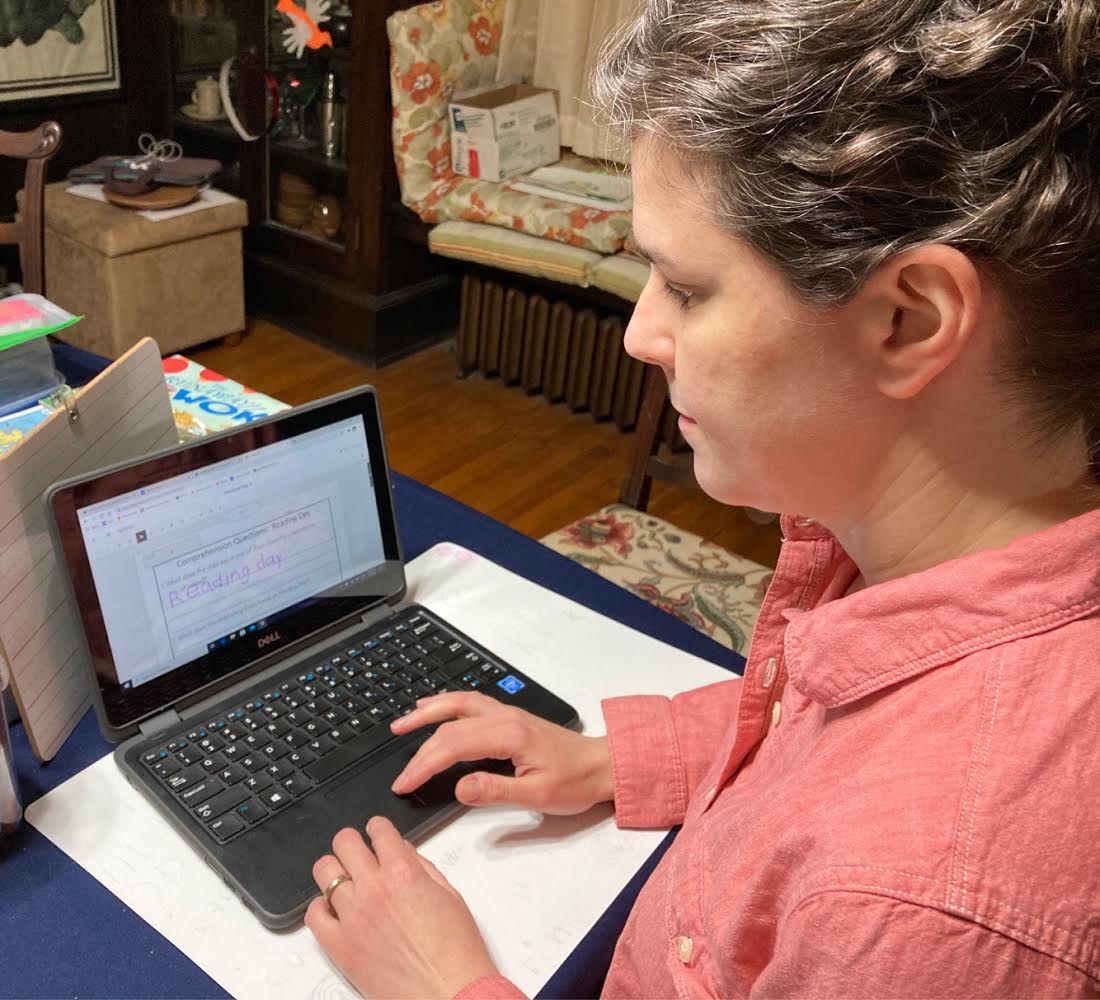

Amy Galloway-Barr's work-from-home setup. (Courtesy photo)

Much of her pre-pandemic teaching was offline: hard-copy books, face-to-face discussion and paper assignments written in pen and pencil. One of the biggest shifts for her this school year was having to do more prep work.

“To convert everything into online material means that you have to change the entirety of the way that you would normally teach it,” she said.

Even more challenging has been adjusting to the district’s continued decision to keep students in remote learning.

“It’s been so difficult because our district keeps saying that we’re going back, and then we don’t go back…” she said. “So we keep thinking and planning for something that hasn’t happened yet.”

Students convene from all 90 Pittsburgh neighborhoods to learn at Allderdice. Since the Pittsburgh Public Schools district shuttered in March 2020, she has done little outside beyond grocery shopping.

Her Pfizer vaccine appointment was long-awaited. After multiple tries, she scored an appointment. “It was like a part-time job to try to secure one,” she said. And on the day of her appointment, she drove to a local Rite Aid, double-masked and, before she knew it, she was back in her car. Partially vaccinated.

Her appointment was quick and “anticlimactic,” but when she left she was overcome by emotion in a way she didn’t expect.

“There was nothing about it that should have made me overly emotional, but I got into my car and I just started to cry because I just felt so relieved,” she said. “Like the end is sort of in sight.”

Written by TyLisa C. Johnson

It was a normal Sunday morning in December for sophomore Alex Kiger when a text from a friend left him horrified.

The text had a screenshot of a group chat that showed his Microsoft Teams school account, with a new account photo featuring a racial slur and posting “very vulgar” comments and slurs to most of his contacts, Kiger said.

He was hacked.

Kiger raced down the steps of his home where he saw his mom, who had received an email from Kiger’s algebra teacher about his account. His teacher eventually got in contact with somebody who could take control and it was shut down a few hours later.

As he recounted the story in late February, his face warmed and his voice quaked.

“The things that were said, I’m not even going to repeat because I would never say it,” he said.

PublicSource reported in November on increased cyber threats and attacks toward students in the new virtual learning environment.

Kiger is one of many students nationwide who have experienced hacks or privacy breaches this school year.

Kiger said it took a couple of weeks to have an account that worked again, though he still can’t see some documents.

The district gave him a new email address and Microsoft Teams account, he said, but had log-in issues. He was granted a guest account, but that account sometimes made it difficult to join classes as teachers often avoid letting in unnamed participants and “guest” accounts to avoid unwanted participants.

When the district reached out to Kiger again, it was to let him know his original account was fixed and had a new password. He logged into the formerly hacked account. Immediately, he saw the same hacked icon photo with a racial slur still there. “My heart literally dropped.”

“I was like, ‘I don’t want to touch this. I don’t want to use this account, anything ever again,’” he said.

He said he thinks the hacking of his account should have been easier to fix. He also still doesn’t know if the district investigated.

“If they ever did some sort of investigation, I obviously wasn’t involved. I don’t know if they ever found out who it was or how they did it,” Kiger said, adding he doesn’t know of anything done to prevent it from happening again.

Alex Kiger, 16, is a sophomore at Taylor Allderdice High School. He is photographed here outside his home in Oakland. (Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

Pittsburgh Public Schools did not follow up on a PublicSource request for more information.

With the mass shift to online learning, the need for the district to protect student data has greatly increased.

The need for the district to communicate directly with families is also growing.

“I don’t think the district has done a lot to actively communicate to parents and students and families about the plans on how to move forward and what’s going to happen in this time and what’s going to happen down the road,” Kiger said.

Still, he finds silver linings in a school year unlike any other. He appreciates that the district didn’t rush people back to school buildings and that teachers have been especially understanding.

He lives with his mother and grandmother and is constantly assessing what situations may be too high risk for his grandmother.

“Online school is really, really difficult. And it’s not the same, obviously,” Kiger said. “And frankly, I feel like I’m learning a lot less. But at the same time … I do not think I’d be willing to go back in the building if, you know, proper safety measures weren’t met all the way, like all throughout the building.”

Written by TyLisa C. Johnson

Like many parents across Allegheny County and beyond, Rochelle Leeper is balancing a lot.

Between her final semester of completing two master’s degrees, her internship as a school social worker, preparing meals and snacks each day and facilitating virtual learning for her three children, she’s exhausted.

“My support keeps saying I’m strong,” she said, “But it’s not about being strong at this point. It’s like I’m juggling and I have to pick which battle needs to be fought, but that is also with the knowledge and the anxiety of understanding that there’s a battle that’s not being attended to right now.”

As a parent facilitating learning at home, she says the gig goes well beyond making meals. It can mean checking that your child hasn’t walked away from the computer, helping them to finish assignments, occupying them during a short break or advocating for your child with the school if learning barriers arise.

“If I had to work a full eight-hour job,” she pondered, “how can I actually effectively do my job to feed my family, and it’s little things like this in the way?”

She said she and her children — JuNise, 10, Jamar, 6, and Jamier, 3 — have each struggled in different ways with the pandemic.

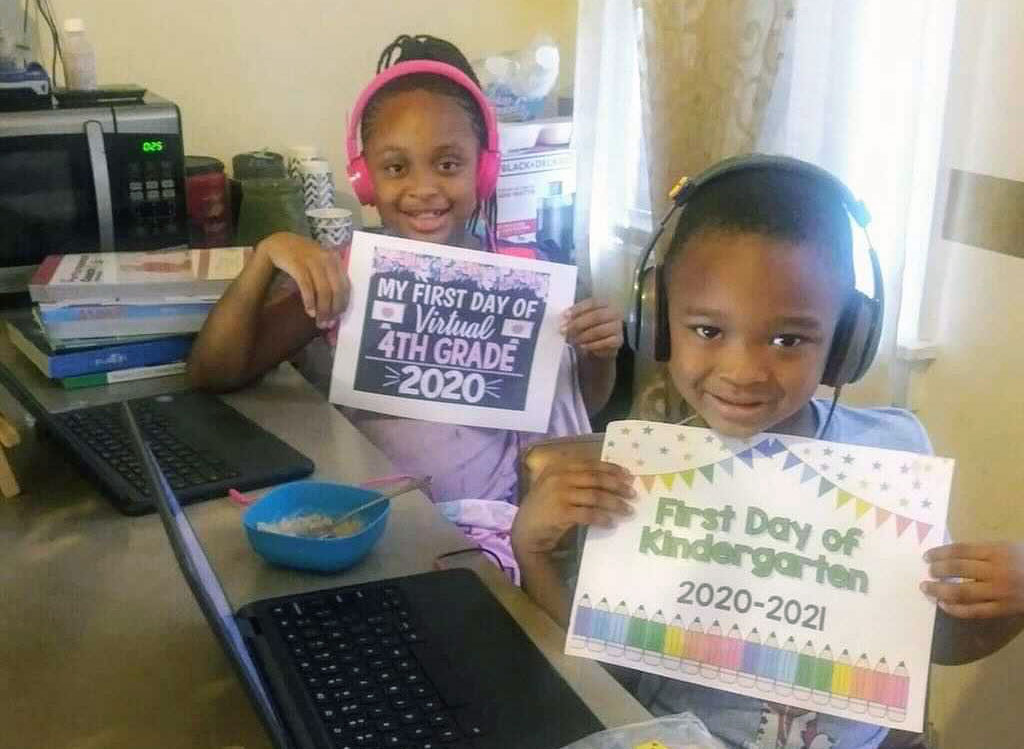

Jamier is at their North Side home full-time after Leeper pulled him from an early education program following COVID outbreaks in the facility in the fall. JuNise and Jamar are in virtual learning at Young Scholars of Western PA Charter School.

JuNise tells Leeper she’s depressed and wants to be in class. The 4th grader, who has a speech impediment and corresponding individualized education plan [IEP], has regressed over the year, Leeper said.

“The tools that she would normally get in person, they’re not really able to get them,” she said. “And again, I see the teachers doing the best they can to improvise, but some things just need to happen in person.”

While some resources work virtually, like mental health counseling, Leeper has found it impossible to address the IEP plan. “I feel like there’s still so many barriers because everybody’s learning and then it’s like while you’re learning as the adult, you’re asking the child to actually learn as well,” she said.

Leeper said she partly wished this year could have been taken as an opportunity for some students to catch up, to build on knowledge already there.

“I just felt like they didn’t give the parents enough grace,” she said.

Her son Jamar is “just over it.” She feels bad for him. To spice up his kindergarten days, he wears a different superhero costume mask to his virtual school each day. Sometimes it’s Iron Man, sometimes Spider-Man or Batman.

Her little boys are constantly bursting with energy, wanting to run and play, jump and flip around the house.

One thing she’s especially grateful for this year was the chance to learn her kids’ learning styles up close. It will make her a better advocate.

As the education community, or “village,” moves forward, including parents, teachers and state legislators, she said it’s imperative that we have a plan. Though some students thrived, others fell behind, so instead of focusing on some success rates, schools should create overarching policies and plans “for if, and when, this happens again.”

She also sees this moment as an opportunity to reframe what kind of education is provided to children.

“The whole idea of the way the school is going right now, they do need to reconsider it for everybody,” Leeper said, “because my kids are getting the same education as I got and times have changed.”

Written by TyLisa C. Johnson

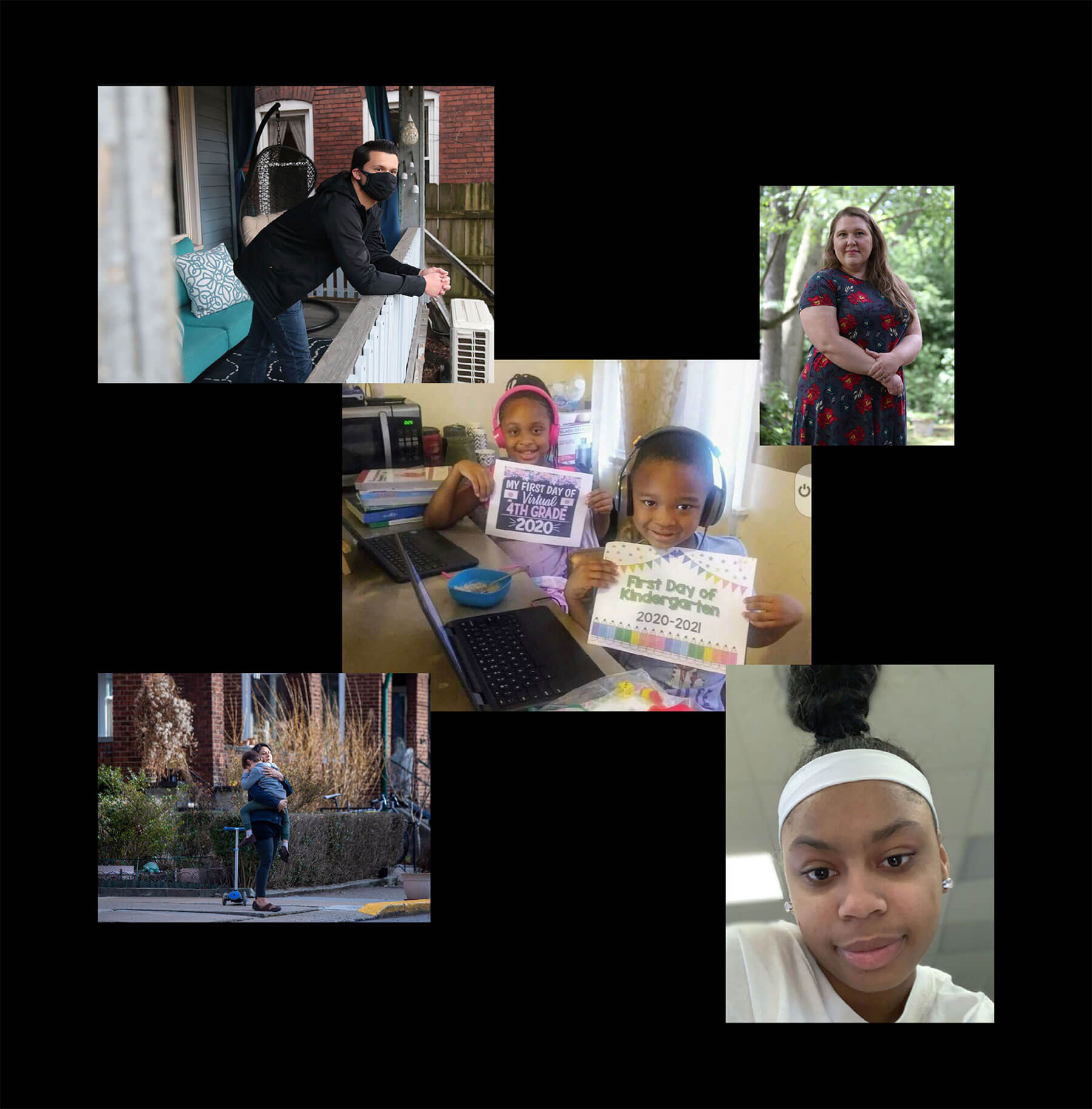

For Rachel Masilamani and her 5-year-old son, Malcolm, the pandemic has only further highlighted the flaws in the nation’s systems for child care and flexible working environments for parents.

“I think we as a nation need to resolve our lack of a national childcare system,” Masilamani said.

The opportunity to work from home has only strengthened her opinion that companies can be more accommodating to parents.

“We as a country have not been here for parents when we should have been,” Masilamani said. “I know my personal situation is not terrible, but it’s not easy either. I can’t make progress or do anything right now. I’m just trying to take every day one day at a time.”

Rachel Masilamani and her son Malcolm in her neighborhood near Wilkinsburg.

(Photo by Jay Manning/PublicSource)

In terms of her son’s education, Masilamani applauds the teachers and staff who made virtual learning possible and consistent for students with special needs. Masilamani’s son receives occupational speech and developmental therapy.

“I watch Malcolm’s teachers and his special needs teachers do amazing work with really just their voices and faces,” she said, “and they’ve been able to build relationships and skills to create an environment that I’ve really been impressed by.”

Written by Punya Bhasin